Identifying the problem

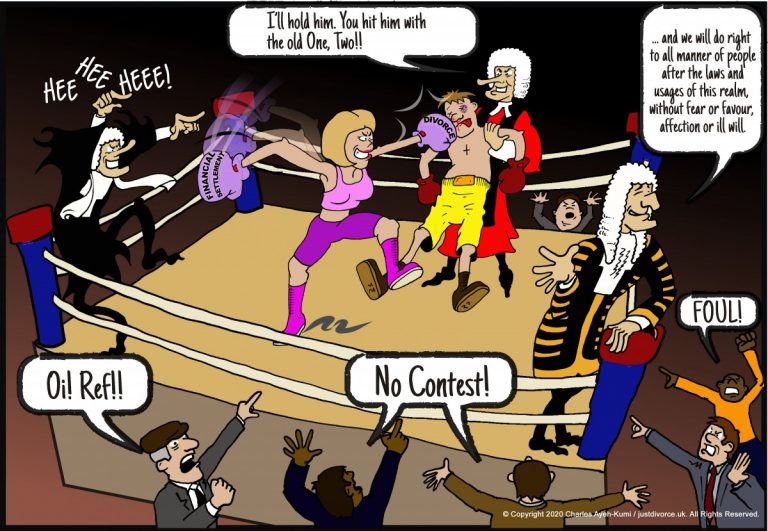

The England and Wales divorce and financial settlement laws are centred around The Matrimonial Causes Act 1973. (MCA 1973).There are two main aspects to this statute, divorce and financial settlement.

It is stated in legal text books and by judges that sections 1.2.(b), 23 and 25 of the MCA 1973 are vague and nebulous. The wording of these sections is so ill-defined that a legal coach and horses can be driven through them. That is precisely what the family courts and the legal profession are doing.

The Law Society stated in their divorce research document “A Better Way Out” – 1979

“…. The evidence presents little difficulty – after several years of marriage, virtually any spouse can assemble a list of events which, taken out of context, can be presented as unreasonable behaviour sufficient on which to found a divorce petition ….”

The three sections of the MCA 1973 mentioned above, 1.2.(b), 23 and 25, each confer unfettered discretion on the courts, ie, the wording of the law sets no constraints or limits on what the judges can do. This lack of boundary infringes the principles of legality and certainty enshrined in the Rule of Law.

Lord Bingham in lectures and also in his book, The Rule of Law (Penguin Books 2010), has said the following about the first principal of the Rule of Law:-

First, the law must be accessible and so far as possible intelligible, clear and predictable. This seems obvious: if everyone is bound by the law they must be able without undue difficulty to find out what it is, even if that means taking advice (as it usually will), and the answer when given should be sufficiently clear that a course of action can be based on it. There is English authority to this effect, and the European Court of Human Rights has also put the point very explicitly:

"… the law must be adequately accessible: the citizen must be able to have an indication that is adequate in the circumstances of the legal rules applicable to a given case … a norm cannot be regarded as a ‘law’ unless it is formulated with sufficient precision to enable the citizen to regulate his conduct: he must be able – if need be with appropriate advice – to foresee, to a degree that is reasonable in the circumstances, the consequences which a given action may entail."

Obvious this point is, but not, I think, trivial.

Whether derived from statute or judicial opinion the law must be stated in terms which a judge can without undue difficulty explain to a jury or an unqualified clerk to a bench of lay justices. And the judges may not develop the law to create new offences or widen existing offences.

“The law must be accessible and so far as possible intelligible, clear and predictable.

Why must it?

I think there are really three reasons. First, and most obviously, if you and I are liable to be prosecuted, fined and perhaps imprisoned for doing or failing to do something, we ought to be able, without undue difficulty, to find out what it is we must or must not do on pain of criminal penalty. This is not because bank robbers habitually consult their solicitors before robbing a branch of the NatWest, but because many crimes are a great deal less obvious than robbery, and most of us are keen to keep on the right side of the law if we can.”

(see the section on The Rule of Law for a fuller explanation of the Rule of Law.)

Section 1.2.(b) is the so called “Unreasonable Behaviour” clause that forms the basis of nearly 60% of all applications for divorce.

Sections 23 and 25 of the MCA 1973 are the two clauses that give the courts authority to adjudicate on financial settlement issues.

The lack of clarity in the drafting of sections 1.2.(b), 23 and 25 gives the courts no guidance and no boundaries to work within. Instead these sections give judges unlimited discretion to interpret the statute law according to their collective view.

Unconstrained discretion is explicitly against the Rule of Law. It is bound to lead to inconsistent and arbitrary outcomes as each court and each judge applies their own interpretation instead of a uniform interpretation (common law).

46. “Law” covers not only constitutions, international law, statutes and regulations, but also, where appropriate, judge-made law, such as common-law rules, all of which is of a binding nature. Any law must be accessible and foreseeable.

Unfettered discretion is contrary to the Rule of Law principles of certainty, predictability and protection from arbitrary decisions.

(see the section on The Rule of Law for a fuller explanation of these concepts.)

In Marckx V Belgium, the European Court for Human Rights stated:

‘the object of the Article [8] is “essentially” that of protecting the individual against arbitrary interference by the public authorities.